“Do you guys see the elephant head?”

The burl had transformed from two lovers embracing to a parent cradling a child to now a single elephant head. I imagine my brain bending its original outlines to mirror some deep-rooted desires and fears like a natural Rorschach test or an earthy companion to cloud spotting, finding small reflections of self in amorphous ambiguity. Its shape usually shifts with ease, but this time, a manifestation of multiple psyches at work — a collective pareidolia of park regulars — has reconstructed the figure, and for the last few months, as first pointed out by the cairn terrier owner in blue, I see nothing but an elephant head.

To an arborist, however, it is still very much a tree. The determinants of our human eyes do not change its nature.

Burls are still a mystery in science. Although their official etiology is unknown, their hardened form is often compared to scar tissues, tumors, or calluses — a potential walled-up mechanism to protect the rest of the tree from stress, such as insects, illness, or injury. This response, a mosaic of hyperplasia, is generally considered harmless, benign, and nonfatal to trees and does not call for pruning. They exist as symbols of resilience and, like other other bodily badges of endurance, can ignite scorn, pity, or awe in the faces of onlookers. A gnarled mass of what should have grown into a simple branch complicating our categorical, black-and-white understanding of living and dying.

ᝰᯓ

The acronym for deep infiltrating endometriosis is DIE, the lead suspect of my chronic abdominal pain. Endometriosis is a condition in which tissue similar to the lining of the uterus grows, bleeds, and sheds outside the uterus, but unlike normal uterine lining, they have no way to exit the body, leading to a buildup of inflammation and scarring. When these tissues start penetrating other organs within the pelvic cavity (DIE), they can cause a condition in which these organs become “glued” together and immobilized due to the development of adhesions. Before knowing the medical explanation of this phenomenon –– unofficially called a frozen pelvis –– I could only describe this painful and uncomfortable “big stuck” feeling in my lower abdomen area as a contorting burl of my own, sitting in and warping the base of my belly. I feel its presence in every physical movement. In recent days, I have found that self-confinement and stillness are the best solutions for dulling its occupancy.

Because of the area “endo” presents itself in, the discussion of life is often brought up during my doctor appointments, specifically in regard to preserving fertility. I wonder how many people have grieved this part of their journey. I think about the grief I carry because of my illness: canceled trips, sunny days I spent in bed instead, financial debt, friendships, the simplicity of walking around the park with ease and seeing the elephant tree. The grief is not much different from when I was a depressed teenager. The disease is a survivor as much as its host –– it has its own repeated cycle of defeat and resurgence. Many of those suffering from endometriosis will undergo surgery –– a diagnostic tool and treatment plan –– to alleviate pain and reduce complications, which, in return, can produce new scarring, leading to nearly half of patients experiencing recurrences and, therefore, repeating procedures every few years, often until menopause when endometriosis ceases. There is grief in knowing this as I wait for my first surgery.

Endometriosis is considered a nonfatal disease. In a medical sense, this brings me comfort. But in reality, I’m well aware of the little deaths in living. Ask any survivor. To survive is to grieve –– a viscous binding, a big stuck. It tightly jerks you back and forth between the small margins of life and death.

ᯓᯓ

When you cut a burl from a living tree, it creates a greater wound and weakens the entire unit, ultimately killing the tree. Although burls act as a safeguard, their unusual disfigurement sometimes makes them targets for eradication. To those who do not see an embrace or an elephant head, a burl’s unruly shape can be uncomfortable and unsightly. To others, burls are valuable jewels waiting to be mined –– their unearthly patterns beneath make beautiful furniture that mimics coffee and creamer swirling in a cup.

Sometimes, I imagine going to the park and seeing the tree without its elephant-head appendage. I am not an arborist. I could not tell you if this tree is alive or dead. The last time I saw it, I stared at two small hollows that looked like eyes. It stared back at me -– in that moment, it was alive.

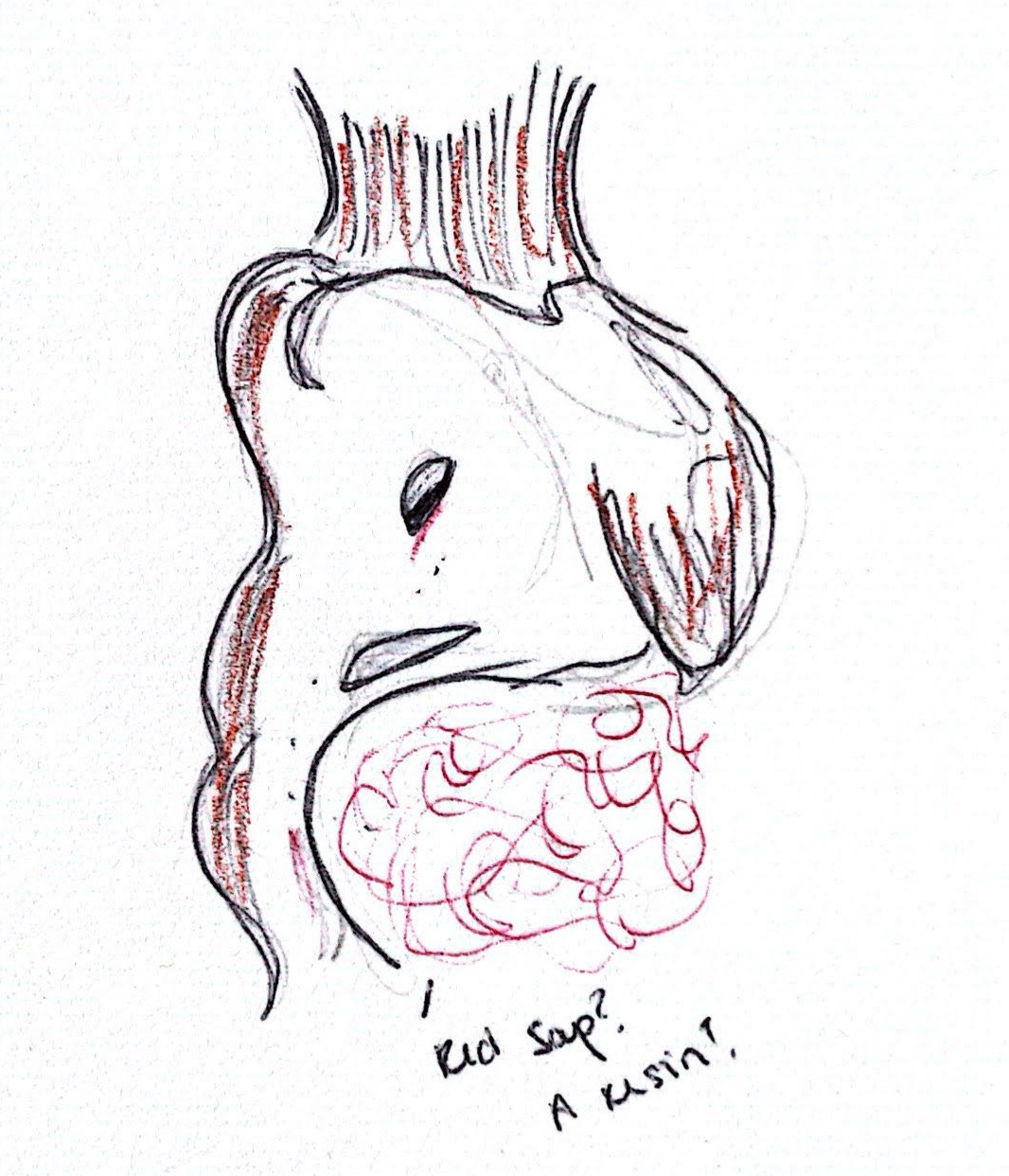

When I looked closer into its crevices, into the parts where it’s just a tree and not an elephant, I noticed a line of ants feasting on a red ooze.

THE COMPOST

Thank you for reading my first post. This newsletter exists as a creative nature journal dedicated to my experiences as a queer and disabled person living in the swamplands of Southwest Florida. These mini essays are my way of documenting my complex love for this complex land, as well as my complex interpretations and thoughts that could only derive from a place like here.

This part of the newsletter is for you. It will offer prompts and instructions to help you begin your own nature journal, whether you keep it on paper or carry it in your mind. Let it be a guide to the many worlds around and within you.

Go to your backyard or local park. Notice a tree with characteristics that stand out to you. It could be a hunky, gnarly beast or a withering Charlie Brown Christmas tree. Outline its shape in a sketchbook with a pencil or in your head with your eyes. Do it more than once. What figures do you see, and what do these figures mean to you? Do you see death or life?